Our own Robin (staticnrg)'s blog - http://survivethejourney.blogspot.com - is mentioned at the end!

This week the Grand Round will be hosted by Invisible Illness Week, a blog dedicated to the National Invisible Ilness Week, which runs September 14 -20, 2009. The purpose:

National Invisible Chronic Illness Awareness Week (..) is a worldwide effort to bring together people who live with invisible chronic illness and those who love them. Organizations are encouraged to educate the general public, churches, healthcare professionals and government officials about the impact of living with a chronic illness that is not visually apparent.

The theme of the Grand Round is, not very surprisingly: Invisible chronic Illness.

I won’t write about this professionally -being a librarian-, but I will speak from my own experience.

As many of you know, I’ve the chronic illness Addison’s Disease. Not that I feel ill. It doesn’t affect me, really… Not anymore.. I think.

But many people with Addison’s disease suffer silently from this disease. And like many other diseases this disease is seldomly understood by partners, colleagues, friends ….. and doctors.

Before I explain more about Addison’s disease, first let me say that almost every disease is “invisible” to others. People can never fully understand what an illness means to someone suffering from it.

Cortisol, Image via Wikipedia

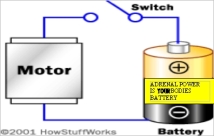

Patients with Addison’s disease make no or too small amounts of cortisol, a hormone made by the adrenal cortex. Cortisol has a bad reputation as the stress hormone among many people. It doesn’t deserve this reputation as this hormone is vital to life. Corticosteroids are involved in a wide range of physiologic systems such as stress response, immune response and regulation of inflammation, carbohydrate metabolism, protein catabolism, blood electrolyte levels, and behavior (Wikipedia)

Too much of this hormone causes Cushing’s disease, too little causes Addison’s disease. If you want to know what Cushing does to your body and mind, then please read the letter of Kate when she was first diagnosed with Cushing’s, at Robin’s “Survive the Journey”.

Here, I will confine myself to Addison’s disease. It is a very good example of an invisible yet serious disease.

There are 3 forms of Addison: primary (defect in the adrenal cortex itself, often also leading to a defect in aldosteron production), secondary Addison (by a defect in the hypophysis or hypothalamus) and iatrogenic Addison (caused by overtreatment with corticosteroids)

Here some reasons why the illness, although “invisible”, can have great impact on your live.

1. Diagnosis.

well-ville.com/images/adrenalQA2.jpg

Diagnosis is often a challenge, especially in patients with primary Addison, most of whom look healthy because of their pigmented skin. Nowadays, the main cause of primary Addison’s disease is immune destruction of the adrenal cortex. This has often a slow onset and in 50% of the patients the diagnosis takes more than 2, sometimes even more than 10 years [1]. 38% of the patients even experience vague complaints, that can later be attributed to Addison, during 11->30 years before diagnosis [1].

Before the diagnosis is made, people with Addison’s Disease often feel extremely tired and miserable. Even when the disease fully manifests itself the symptoms are largely vague and aspecific. The most common symptoms are fatigue, dizziness, muscle weakness, weight loss, difficulty in standing up, vomiting, anxiety, diarrhea, headache, sweating, changes in mood and personality, and joint and muscle pains. Often the symptoms aren’t taken seriously (enough) or the illness is mistaken for anorexia or depression.

My secondary Addison was the consequence of an injury to the pituitary gland as result of heavy blood loss during complicated childbirth (see previous post). The week between the cause and the diagnosis of the disease, was the most terrible week of my life. I felt awful, weak, (well I lost >3 liters of blood to start with), couldn’t give breast milk (no prolactin), and I disgusted food so much, you can’t imagine. I couldn’t get anything down my throat, only the look of it made me vomit. And I felt so bad not being able to care for the baby, but I just couldn’t. I couldn’t even stand for more then a few minutes, couldn’t walk. And then there was unstoppable diarrhea, dizzyness, and speaking with double tongue. And practically no one took it seriously, not the gynaecologists, not the nurses, not the paediatricians, nor my friends or family.

But this was only one week. How would it have been if it durated 5 or 10 years?

2. Grieve and adaptation.

Once the disease is diagnosed you have to learn to live with a body that has let you down (grieve) and you have to learn to become confident again (adapt). You also have to find a new balance. I’ve lost a few hormones overnight (ACTH, cortisol, thyroid hormone, growth hormone, prolactin, gonadotrope hormones) and believe me, it took me a few years to feel reasonable normal again. It is quite surprising how badly I was informed. Very little information about the risk of an Addisonian crises, the dosing of cortisol under various conditions.

It was also confronting how little people wanted to know about the disease or what I had been through. Visitors after the birth wanted me to be euphoric and didn’t want me to go into any detail of what had happened. They cut me short by saying: “But you have a lovely baby”. Somebody cried that she didn’t want to hear it. So I stopped trying to speak about it.

I took no sick leave, immediately went back to work. My boss – a nephrologist, never asked after my health, not once.

As I said it took a few years before my “come-back”. I didn’t feel myself. It was as if I couldn’t think, as if my head was filled with cottonwool. Afterwards I think the main reason for improval was the reduction of the cortisol from 30 mg to 12.5 per day and the use of DHEAs plus that I regained confidence in myself.

3. Comorbidity

With cortisol I lost some other hormones which are also essential. Patients with primary Addison often miss aldosteron as well, which makes them more liable for an Addisonian crisis. Primary Addisonians may also have other immune diseases, like autoimmune thyroid disease, gonadal failure, type 1 diabetes and vitiligo.

4. Addisonian crisis

An addisonian crisis is an emergency situation, with possible fatal outcome, associated mainly with an acute deficiency of the glucocorticoid cortisol. This occurs in (extremely) stressful situations. Some Addisonpatients are more prone to it than others. You can -and should – take precautions, like wearing alert bracelets or necklaces, so that emergency personnel can identify adrenal insufficiency and provide stress doses of steroids in the event of trauma, surgery, or hospitalization.

Some Addisonians fear these crises so much that they dear not walk or run alone. Many Addison patients don’t go to a country far away, some don’t even pass the border (and you know the Netherlands aren’t that big).

5. Addison’s disease can be treated but not cured.

Addison patients are treated with corticosteroids like hydrocortisone and are substituted with other hormones that they may lack. Without treatment, the disease is lethal, with treatment the disease is not cured. I do feel all right now, but many of my fellow patients don’t. I think that the following excerpt from a Seminar of Wiebke Arlt and Bruno Allolio about adrenal insufficiency [2] makes this very clear.

Despite adequate glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement, health-related quality of life is greatly impaired in patients with primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency. Predominant complaints are fatigue, lack of energy, depression, and anxiety. In addition, affected women frequently complain about impaired libido. In a survey of 91 individuals, 50% of patients with primary adrenal insufficiency considered themselves unfit to work and 30% needed household help. In another survey of 88 individuals the number of patients who received disablility pensions was two to three times higher than in the general population. The adverse effect of chronic adrenal insufficiency on health-related quality of life is comparable to that of congestive heart failure. However, fine-tuning of glucocorticoid replacement leaves only a narrow margin for improvement, and changes in timing or dose do not result in improved wellbeing.

References

- Zelissen PM. Addison patients in the Netherlands: medical report of the survey. The Hague: Dutch Addison Society, 1994.

- Wiebke Arlt, Bruno Allolio. Adrenal Insufficiency, Lancet 2003; 361: 1881–93 , full text on http://www.addisonssupport.com/Documentation/adrenal-insufficiency-2003.pdf

Earlier posts on the subject:

- http://laikaspoetnik.wordpress.com/2008/10/19/changing-care-for-addison-patients/

- http://laikaspoetnik.wordpress.com/2008/10/27/the-importance-of-early-intervention-in-an-addisonian-crisis/

Related articles by Zemanta

- Multimorbidity, and why it’s difficult to care for complex medical patients (kevinmd.com)

- Dear Family and Friends…. (survivethejourney.blogspot.com)

- Please Don’t Ask Me ‘How are You?’ (somebodyhealme.dianalee.net)

From http://laikaspoetnik.wordpress.com/2009/08/17/invisible-chronic-illness-addisons-disease/

0 comments:

Post a Comment